Carmel was born in 1827, the third child of Martina Castro (the family for whom Castro Street is named). Her father was Simon Cota, a Spanish soldier who died shortly after she was born. Carmel inherited her boldness from Martina—the first woman to ask for and receive a Spanish land grant, Rancho Soquel, which amounted to 34,000 acres along the coast south of Santa Cruz. Carmel was raised on Rancho Soquel during the time the hide and tallow trades were booming and life on the rancheros of Mexican California was one of comfort and ease. She had seven sisters (Martina had nine children) and, known for their hospitality, they hosted many parties and celebrations.

Carmel was born in 1827, the third child of Martina Castro (the family for whom Castro Street is named). Her father was Simon Cota, a Spanish soldier who died shortly after she was born. Carmel inherited her boldness from Martina—the first woman to ask for and receive a Spanish land grant, Rancho Soquel, which amounted to 34,000 acres along the coast south of Santa Cruz. Carmel was raised on Rancho Soquel during the time the hide and tallow trades were booming and life on the rancheros of Mexican California was one of comfort and ease. She had seven sisters (Martina had nine children) and, known for their hospitality, they hosted many parties and celebrations.

Martina's second husband Michael Lodge was killed in the goldfields of 1849 and she quickly married a third time to Louis Depaux—it was an unhappy marriage. She divided her land holdings evenly among her children and herself to ensure that Depaux would not inherit in the event she died. Carmel inherited one-tenth of Rancho Soquel, 3400 acres of land.

In 1849, Carmel married an Irish businessman, Thomas Fallon, a hotel and saddle shop owner in Santa Cruz. He was a handsome and charismatic ladies' man, ambitious for money and power. It is more than likely that he married Carmel strictly for her money.

Being the no-nonsense woman that she was, Martina knew that Tom Fallon was a scoundrel. She hated Fallon from the start and sued him repeatedly in an unsuccessful attempt to prevent him from inheriting half of Carmel's land wealth.

Carmel and Tom sold the 3400 acres of land and moved around, eventually settling in San Jose by 1854. Tom Fallon became the first Mayor of San Jose in 1859. That same year construction was completed on the San Jose Fallon House, an opulent Italianate home, the first of it's kind in San Jose, which in the mid 1800's was still a land of Spanish ranchos and austere adobe dwellings. The Fallons lived in San Jose until 1876. During this time Carmel had six children (they had nine altogether, three of whom died of cholera).

On the evening of December 9, 1876 Carmel returned home unexpectedly to find her husband engaged in what papers called "a compromising position" with the housekeeper Maggie McBride

It was the last straw for the headstrong Carmel who should have listened when her mother said she didn't like Tom Fallon. Carmel whipped the adulterers with a fireplace poker, packed her bags and moved out the next day taking her four unmarried children with her to San Francisco.

After twenty-seven years of marriage, Carmel sued for divorce, charging Tom with adultery, mental cruelty and physical abuse. Tom married again briefly, and his second wife also accused him of severe abuse. Maggie McBride sued Carmel for assault and battery and slander resulting in loss of her good reputation. McBride won the suit for assault but not for slander, and the court required Carmel to pay McBride nine-hundred dollars.

Carmel started over as a business woman in San Francisco with a tidy sum of $30,000 in gold, the equivalent of $3 million with 1998 inflation, and property at the northwest corner of Third and Minna, where she had The Hotel Carmel built. Savvy with real estate, she also had the Fallon Hotel built at 1693 Market which now contains Albert Schilling Spice & Chocolates. In 1894, Carmel had 1800 Market built and lived there until her death in 1923.

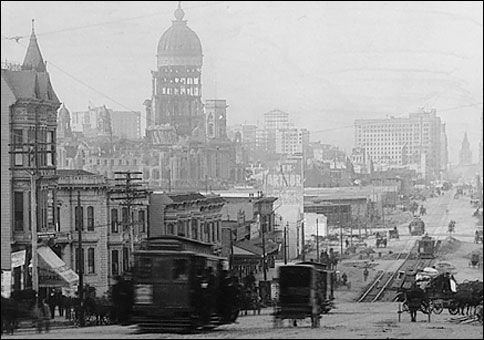

While the Fallon Building (depicted on the left in the image above) survived the earthquake and fire of 1906, Carmel suffered from poor health for the rest of her life. Though no one knows for sure, it is likely this brave woman suffered smoke inhalation from battling the flames that threatened her home.

Carmel's fortune grew to $500,000 by 1923. The bulk of her estate was willed to her daughter Anita Fallon, an actress at Golden Gate Theater —also known by the stage name Annie Malone.

Carmel's fortune grew to $500,000 by 1923. The bulk of her estate was willed to her daughter Anita Fallon, an actress at Golden Gate Theater —also known by the stage name Annie Malone.

Around 1921 Carmel made a generous pledge to the Opera House that wasn't paid until the War Memorial Trustees sued her estate in 1933 and 1800 Market Street was sold to pay the debt. There's a plaque in the San Francisco Opera House which bears the name of Carmel Fallon.

Courtesy of The Noe Review, February-March 1998

THE SAN JOSE FALLON HOUSE

When Carmel left San Jose in 1876, Tom also moved out, often staying in hotels in San Francisco. The Fallon House remained unoccupied until 1900 when it was redesigned into an Italian hotel and restaurant. It was closed 1991 when the City of San House bought the house for preservation purposes. Most San Jose residents think of the Fallon House as a place to dine on Italian food.

As the first mayor of San Jose, Tom Fallon has left his mark on the city's history. So, while many of San Jose's older buildings have been demolished, Tom and Carmel's mansion was targeted for preservation.

The Fallon House and adjacent Peralta Adobe comprise San Jose's Historic District, each home representing the different cultures that originally settled in San Jose. The Adobe is small and rustic, an example of how the Spanish lived in modest dwellings and displayed their wealth in vast land holdings and heads of livestock. The Fallon House, by contrast, is ostentatious, an example of the way Anglo-Saxons display wealth.

Tom McEnerny, mayor of San Jose from 1983-1990, was the mover and shaker who brought about the formation of San Jose's historic district. "I saw all the old buildings being lost to the wrecking ball," he says. "They were building all these high-rises—and we were losing our history. In 1988 I got the city of San Jose to buy the two buildings for restoration. It was expensive but I can't think of a better investment than preserving our history."

Restoration was completed in 1994 and the buildings were opened as museums. The Fallon House alone cost around $4 million to acquire and restore, including structural reinforcement, cleanup, cosmetics and vintage 1850's: furniture, carpets, paintings, and other furnishings.

The Fallon House is painted beige with chocolate brown trim and stained wood arches above the front doors—an anachronism, surrounded on all sides by faceless midrise office buildings. During the week the Fallon and Peralta homes are filled with groups of touring schoolchildren.

Today is a rainy Sunday and there is a small group of adults taking a tour. Sally Beaupre, a volunteer docent, unlocks the front door. The house is expansive with high ceilings and a long stairway with paisley green carpeting that leads to the second floor. We are immediately wowed at the carefully hand painted wood floor made to look like small green and white tiles.

"This is a piece of the original floor," says Beaupre. "It was originally made out of oilcloth, probably because oilcloth was easy to keep clean." The oilcloth is green and white, so the floor is obviously an authentic replication.

"No one knows for sure what the furnishings looked like when the Fallons lived here," says Beaupre. "Most of what you see here is the way we think it may have looked."

The first door to the left opens on the sitting room where the wealthy Fallons invited guests and probably where Carmel caught Tom engaged in the dastardly deed with the maid. On the walls are muted paintings of San Jose when it was nothing but rolling hills and the Hetch Hetchy valley before it was dammed for a reservoir. Over the fireplace in the dining room is a picture of Carmel Fallon in her thirties. Her hair is long and carefully curled.

"You can see that curling irons in the 1800's looked almost the same as they do now, only they had to be heated in the fire," says Beaupre. The kitchen has a "dry sink" made of wood. "There were no faucets so water had to be pumped from an outside well," says Beaupre. "The maids did the dishes in pots and poured the dishwater out in the backyard."

Upstairs, are high archways with white cherub faces. It was a posh lifestyle even without the running water. Today, San Jose's Fallon House Museum is a tribute to Mayor Tom Fallon though it was originally built with Carmel Fallon's money. This suggests that San Francisco's Fallon Building should be restored to its original beauty, at least on the outside, as a fitting tribute to an unusually liberated woman who risked her health to save it. Who knows, Carmel might have been mayor herself if the times had allowed it.