Architecture can be viewed variously as a series of styles, as the development of functional solutions of socio-economic problems, as a transmitter of cultural values, etc. Architecture may also be viewed from the point of view of gender: the sense of the masculine or feminine is obvious, but also a sense of the queer, or other more complicated communications of gender.

Gender has always been explicitly or implicitly a subject and object in architecture, whether in terms of function, realms and modes of habitation, or whether in terms of the perceived or agreed upon masculinity or femininity of a particular formation or inflection of style. The Rococo, Flamboyant and Ionic styles, as well as the work of Bruce Goff, are felt to be feminine. The Norman Romanesque, a vein of the Renaissance architecture of Spain (El Escorial), the Doric and the work of Le Corbusier are felt to be masculine. We look at the photograph of the bedroom of a movie actress from the forties with its rococo touches as channeled by Cecil Beaton and say, "Of course, this is queer space." We look at the muscular architecture of Chandigar or the Seagram building and we do indeed feel as though we are in a brave new man's world of serious masculine men doing serious things.

At times, this expression of gender has been explicit and conscious, and at other times it has been unconscious. The Greeks intentionally meant the Doric to be masculine and the Ionic to be feminine and had legends concerning these orders expressing this sense. Modernism at its inception was as much as anything else a reaction against what was seen as the decadence and effeminacy of the various national "art nouveau" styles ("liberty style" in Italy, arte moderna in Spain, jugendstil in German speaking countries, the Craftsman movement in England, the work of Plecnik in Slovenia). Modernism was supposed to be a universal style devoid of not only what was felt to be an anti-socialist nationalism, but what was also considered to be a perverted eroticism and sentimentality. This is clearest in the thought of Adolf Loos:

The urge to decorate one's face and anything else within reach is the origin of the fine arts. It is the childish babble of painting. But all art is erotic.

A person of our times who gives way to the urge to daub the walls with erotic symbols is a criminal or degenerate. What is natural in the Papuan or the child is a sign of degeneracy in a modern adult. I made the following discovery, which I passed on to the world: the evolution of culture is synonymous with the removal of ornamentation from objects of everyday use.

— Adolf Loos, Ornament and Crime (1929) (1).

Aside from a communication through architecture of the sense of the masculine and feminine, it has been argued by Aaron Betsky and others that queer space can also be identified as a communicated sensibility. He argues that "queer space" has been historically by nature an evanescent, theatrical, pagentlike, anarchic, exaggerated, and marginal phenomenon; that is has to do with the transformation of the normative space into something other, by turns more domestic or more exaggerated, always more sensual. (2)

It has also, by and large not been consciously designed as queer space; it has either "just happened" or only consciously expressed the taste of gifted individuals with few other motives beyond the personal. A specifically Lesbian sense of space is harder to trace, although a distinct feminine chthonic sensibility may be traced from the temples of Bulgaria to Knossos to the work of Mary Colter. This sensibility seems of a different tone than Betsky's conception of "Queer Space" as it is massive, non-cartesian, earthy and permanent in feeling and requires it own examination in terms of the role of gender in architecture.

It is clear that aside from the conscious intent of Modernism not to transmit cultural values such as national identity, and its demonizing of such intent to transmit those values, that such values can be transmitted by architecture and have always been transmitted quite successfully. An example of this might be found in the various art nouveau modes preceding Modernism. The specific and explicit intent of these modes was the communication of national and/or ethnic identity.

A good example of this is the Palau de Musica in Barcelona. The Palau de Musica in was built a manifestation of, proof of, discourse upon and setting for Catalan identity and culture at a time when the existence and continuity of Catalan culture was in question. The architecture manifests these aspects through form, color, and explicit and implicit symbolism, ornament and historical stylistic reference. The point of the aesthetic, social, and political success of the Palau is that architecture can indeed be the successful transmitter of complex cultural values and sensibilities.

It is a new and unprecedented occurrence that with the existence of GLBT institutions, and their reaching an age and maturity in which they need permanent facilities, there arises the new possibility of public, non-commercial intentional queer space in the world. Since there is historically a thread of gay sensibility in the inhabitation in the space, in being in the world which has almost always been expressed unconsciously or unintentionally, how will it now be expressed consciously and intentionally? How should the new public GLBT space be created and experienced within the context of its particular function, and what should it communicate of queerness to the various GLBT clients and users and to the larger culture?

The philosophy and methods of Modernism offer tools not of much use for an approach to this problem. Modernism presents itself as a culturally neutral style, born of its end place in a human history seen as solely as an evolution of technology, through which local cultures are supposed to express their climates and cultural functions to produce colorful local variants on the modern theme, all the while conforming to the modern ideals of functionalism, "honest" use of materials, the immorality of ornament, industrial materials, absence of historical (both artistic, cultural and national) reference (except to the history of the modern movement itself). However, as we have seen above, Modernism is not really neutral as it carries with it its own bias, culturally, morally and in terms of gender identification.

Far from being a universal style, Modernism is imbued with a peculiarly Northern European prudishness, Puritanism and hyper masculinity. The stripping of architecture of ornament, ornament which usually communicates culture and history (whether national or local or community) was intended to bring the Marxist end of history, but instead has impoverished the possibility of local cultures. Modernism's hyper masculinity can be seen in the cult of the machine, the imagining of buildings as large machines as in the work of Calatrava, and the confluence of the imagery of Science Fiction fantasy and architectural style. This is indeed, "space cowboy" architecture. Bruce Goff, one of the few identifiable queer practitioners trying to work within the strictures of Modernism was essentially marginalized as his work was seen to be too extreme, too "camp."(3) It seems to us that modernist architecture is kept by the defenders of its moralistic formulation to be strictly an expression of a sober masculinity.

Modernism is by nature and philosophy antithetical to the polymorphous erotic conversation possible in architecture. Architects of the new intentional queer spaces now being built and designed need to come up with a different methodology from Modernism, a new morality, or perhaps an old immorality when it comes to the design of the new public GLBT space: an immorality which is able to communicate both the cultural and erotic values and sensibilities we consider or want to have as part of our sub-culture.

Alan Martinez, AIA

April 30, 2002

![]()

(1) Page 167: Adolf Loos, Ornament and Crime, translated by Michael Mitchell, (Riverside, Ariadne Press, 1998)

(2) Page 21: "At other times, queer space displaces the body into materials, decoration, and the manipulation of sensual forms. At its most romantic, queer space wants to dissolve the structures and strictures of society and obliterate the space between the self and the other, engaging in sex as part of a voluptuous extension of the body into an oceanic world. This is perhaps the essence of queer space. If we live in physical orders (buildings) society has imposed on us, queer space finds in the closet or the dark alley places where it can construct an artificial architecture of the self. Having appropriated the imposed orders of society, it then poses an alternative-mirror space-that might let all of reality and the self dissolve into something that is pure sensation or bodily experience." Page 22: "Queers are masters of the hidden gesture, the theatrical walk, the creation of close physical connections through the most fleeting motions of the body. At times, queers have managed to translate gestural language into the very basic building blocks of our cities. Gesture finds its most physical points in buildings that refuse to sit still, obey orders, or tell a simple story of order. Gestural buildings area distorted, distended, and deformed. They break through their skins, move out into space, and speak in ways that are often difficult to understand.

Aaron Betsky, Queer Space, Architecture and Same-Sex Desire, (New York, William Morrow and Co. Inc., 1997)

(3) Page 147: In a letter from Frank Lloyd Wright to Bruce Goff on the subject of the Joe Price Studio design of Goff's: ". . . .I hate to see the thesis I've worked for life-long in Architecture knocked silly according to the prophecies of the too powerful "opposition." Had the travesty been deliberate (at first I thought it was) it probably could not have been half so complete . . . But Bruce, why so elaborate and expensive a fiasco? Why not do a charming little "scherzo" for the lad that could pass as such, please him and do violence to nothing. The thing is practically unbuildable as is; it is practically on the plane of idiocy when its cost is counted. I am sure you can please "the kid" with far less violence to good architecture. . . Originality is not the thing - there is another word for it that I won't use because when this sort of thing appears the more you say against it the more the victims become convinced that genius is in it and that the world is envious. But "sensational" may be at the same time artistic as you ought to know."

FLW, 12/16/54 Delong, David G. Bruce Goff: Toward Absolute Architecture (New York, Architectural History Foundation, 1998)

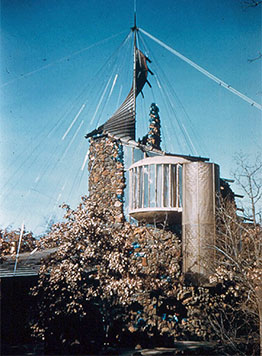

Top to bottom: Work of Le Corbusier (top two images), Jose Plecnic, and Bruce Goff