![]()

Several years ago, a national historic preservation organization held its annual conference in a major Midwest city. At the plenary session, several speakers came to the podium and declared, "I am a preservationist." As the speakers followed one another, the session began to resemble a spiritual revival where true believers declared their faith and allegiance to an over-arching value, in this case, historic preservation. By the end of the session, the audience acknowledged that anyone who believed in the preservation of historic places and other aspects of cultural heritage could wear the "preservationist" label.

What is a preservationist? At heart, nearly every human is a "preservationist." Everyone works to retain a sense of history, tradition, and memory of one's family history, one's community heritage, and national identity. All of us are attracted to historic places throughout our nation and in countries around the world. (How many of us would travel to places that have "no history" and no sense of place?) All of us thrill when we hear the national anthem that recalls the struggles of early nationhood. All of us cherish memories of visits to the homes of relatives where historic memorabilia was examined and discussed. All of us share in the shame of the nation's history of slavery, the relocation of Japanese Americans during World War II, and anti-Chinese riots. All of us are "preservationists."

Some preservation efforts are highly personal journeys through the past where individual and family landmarks and memory are paramount. Some individuals seek out historic residences as a matter of personal choice and psychic comfort. Other endeavors are community-oriented, where individuals and groups organize to maintain or enhance the livability of neighborhoods and enclaves. Still other tasks are aimed at national icons and rituals that bind us together in nationhood.

Many of the preservation pioneers of the pre-1960s era represented the social and intellectual elite of American society, or at least, that is how they are portrayed. They were the ones who could afford to restore historic buildings and influence the course of real estate development projects.

Once government regulatory and incentive programs multiplied in the last quarter of the 20th century, preservation became less dependent on monied interests. Preservation efforts became "democratized." Not only could anyone become involved in preservation work, the range of what was considered "historic" also grew exponentially, from buildings and American antiquity to the cultural practices of living societies and other intangible expressions of culture.

Within the past decade, the preservation establishment discovered that many cultural groups have been preserving their cultural heritage for a long time—centuries sometimes—but their efforts had not been folded into the national effort.

Why doesn't this broad interpretation of "preservationist" apply to preservation activities that are played out in countless cities, towns, and rural areas throughout the country? Too often, the press regards preservationists as an elite band of architectural connoisseurs who guard the nation's heritage from unknowing property owners and real estate developers. Thus, breeding, degreed-education, and rarified backgrounds may appear to be requirements for membership in a selective fraternity of preservationists. Many preservationists perpetuate this image by insisting that preservation efforts should be directed at "pretty buildings," which only they can define.

In actuality, preservation is potentially one of the broadest-based of all citizen-driven "movements." It contains a wide spectrum of professional expertise and experience and citizen activism. Some preservationists work in the field full-time, as historical architects, historians, archeologists, ethnographers, and historic landscape architects. Other preservationists work as lawyers, community planners, and legislators, whose work may strengthen preservation laws and policies.

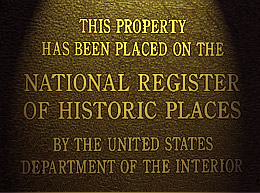

The backbone of preservation was and remains the many citizen activists and property owners, who on a daily basis work to ensure the stability of their communities and maintain their historic properties. The preamble to the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 underscored the central role of citizens and property owners in preservation. This legislation recognized that the major burdens of historic preservation had been borne by private agencies and individuals and that both "should continue to play a vital role." The purpose of government preservation programs was to "give maximum encouragement to agencies and individuals undertaking preservation by private means."

Thus, most preservationists are the ones who lead community associations, write neighborhood newsletters, attend planning and zoning commission meetings, join in community improvement activities, maintain their houses and commercial buildings, and vote for preservation-supporting politicians. They may not be educated in the nuances of the Colonial Revival architectural style, but they are the ones who support government preservation-assistance programs and pay the taxes that fund the salaries of the full-time preservation professionals. They are the ones who support legislation that expands the safety net for irreplaceable heritage.

Preservationists come in all ethnicities, orientations, and ages. They may be drawn to the "movement" through a love of Victorian residences, steam power, Art Deco design, Gothic churches, cast iron architecture, retro-1950s furniture, or regional folklore. They may own and live in a historic house. They may work in a historic commercial enclave. However they arrive at the preservation destination makes little difference. They share a common appreciation for and participate in the preservation of the nation's past.

The next time that your friends or neighbors ask about becoming "preservationists," welcome them. Their inclusion will help expand the political base for future preservation successes. This broad base must exist in order for preservation to become truly an essential building block for the nation of the future. The rising generation of national leaders will want to see that preservation is rich in diversity, is shaped by a myriad of views about the past, and is supported by the multicultural nation. Let us envision the day when all Americans will join hands and each will say, "I am a preservationist."

.Antoinette J. Lee is a preservationist who lives in Arlington, Virginia.

©2002

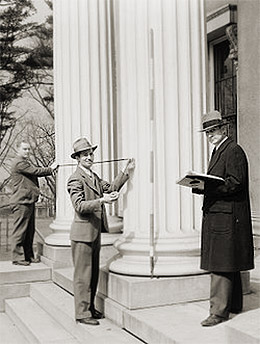

Top to bottom: Preservation stamp 1971; Historic American Buildings Survey Team circa 1934; National Register of Historic Places plaque