Aside from Chinatown or Nob Hill, the Haight may indeed be San Francisco's most famous neighborhood, evoking images of the 1960s counterculture such as the Summer of Love, Janis Joplin and Grateful Dead. However, to students of San Francisco's architectural and social history, the Summer of Love was only one of the most recent installments in the neighborhood's intriguing history. Psychedelic and narcotics aside, the Haight is simply one of the most architecturally coherent, Victorian, streetcar-suburbs surviving anywhere in the United States.

Originally developed as a middle-class residential district in the 1890s and the first decade of the 20th century, the district has gone through several cycles of growth, decline and rebirth, remaking itself in a wholly different cast each time.

The Haight, as we know it, covers approximately thirty blocks bounded by the Panhandle to the north, Central Avenue and Buena Vista Park to the east, Frederick Street to the south and Stanyan and Golden Gate Park to the west. Unlike many San Francisco neighborhoods, the boundaries of the Haight are very coherent due to geography and the location of three major city parks. Its rapid development was inspired by its auspicious location in a natural valley partially sheltered from the worst of the summer fog.

Much of the early history of the Haight can be read in its street names. In 1870, Governor Henry H. Haight appointed the first San Francisco Park Commission that consisted of Joseph A. Donohoe, J.F. Butterworth and D.W. Connolly. Together these men established Golden Gate Park. Although it would be at least two decades before Superintendent John McLaren managed to transform the thousand-acre parcel from a "sandy waste" into a lush greensward, their act transformed adjacent and virtually worthless real estate from a liability into a valuable investment.

As we have seen in other neighborhoods profiled in this series, transportation was always the crucial ingredient before residential development could occur. The Haight was no different. Prior to the completion of the Haight Street Cable Railroad in 1833, what is now the Haight was a collection of isolated farms and acres of sand dunes, most of which was not graded or developed in any way. The new cable car line, completed in 1883, connected the west end of Golden Gate Park with Market Street and downtown San Francisco. Faithful to the oft-said real estate marketing cliche, "build it and they will come," they came. An article in the October 22, 1889 Examiner noted that "following the cable roads...have come street improvements, gas and water mains, street lights and finally the building of substantial residences."

The initial node of development took the form of commercial structures such as hotels, saloons, and restaurants, concentrated near the cable car turnaround at Haight and Stanyan Streets. As the primary public entry to Golden Gate Park, entrepreneurs made the Haight an entertainment destination in its own rights.

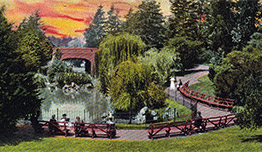

In addition to the California League Baseball grounds (located on the block bounded by Frederick, Stanyan, Shrader, and Waller), there was the Paul Boynton Chute Company's amusement park, located on the south side of Haight between Cole and Clayton Streets. The central feature of the park was "The Chutes," an inclined trestle track that was 300 feet long and rose 70 feet above the ground. Two-car tracks took passengers to a waiting room at the top where they would board gondolas for a return ride down to an artificial lake. "The Chutes" were an early version of a modern flume ride and provided to be very popular. Other attractions in the Boynton amusement park included an elevated railroad track that circulated around the park, various painted panoramas, a merry-go-round, a photo gallery, a "zoological promenade," an alligator house, a theater and an exhibition hall called the "Darwinian Temple."

The Haight's role as a destination for weekend day-trippers continued to dominate the district's economy until the first decade of the twentieth century. However, developers who never miss a trick, saw the possibility of subdividing the area to the west of the park with large single-family homes marketed toward San Francisco's petit-bourgeoisie. Around 1900, "The Chutes" were dismantled and reconstructed further out on Fulton Street, between 10th and 11th Avenues. The lake on the south side of Haight was drained, and Belvedere Street was extended from Waller to Haight. The newly vacant land was then developed from 1902 onward with stores and residences.

A good example of a residence built during the early 1890s is a large Queen Anne swelling at 24 Beulah Street, constructed in 1896 by William Hatteroth. Nonetheless, development along Haight Street itself was stymied by the fact that most of the frontage on either side was owned by the Baird Estate. In the meantime, the blocks between the Panhandle and Haight and the blocks north of Waller developed with rows of Queen Anne style residences.

For the most part, residences constructed in the Haight were two-story, single-family structures situated on 25 foot-wide lots. After 1900, three-story flats were increasingly constructed but the character of the Haight remained largely single-family and middle-class. Unlike working class districts like the Potrero, with houses constructed individually by their inhabitants, the residences in the Haight were developed by a small number of developers and contractors who purchased tracts of land, sometimes as much as an entire block, subdivided them and constructed rows of identical homes. Three contractors active in the Haight in the 1890s and the 1900s include the Hinkel family, Robert Pieper, and Cranston and Keenan.

Regardless of who built them, the residences constructed in the Haight around the turn-of-the-century were generally quite similar. They usually consisted of a high basement/garage with a first floor above consisting of a hall and staircase on one side and a front parlor, middle parlor, dining room and kitchen on the other side. The second floor had bedrooms and a bathroom. The row at 746-60 Clayton is a good example of developer-built housing constructed during the 1890s. Essentially identical inside, the exterior detailing of these bay-windowed and gable-roofed Queen Anne houses varied slightly to increase their "curb appeal." A small back yard and utility shed completed the package. In 1900, houses like these would have sold for around $7,000 and rented for $40 a month. Due to the fact that the Haight was developed almost entirely within twenty years between 1890 and 1910, the Queen Anne style is the predominant mode of design. Indeed, the Haight is the best neighborhood in San Francisco to study the almost infinite variations to be found in this English-derived style.

Although today inextricably associated with the psychedelic sixties, the ebullient Victorians of the Haight were actually marketed toward a conservative middle-class who apparently were sold on the lathe-work gingerbread that still survives on hundreds of residences in the Haight, including 1302-04 Masonic. The 1900 census reveals that the Haight undoubtedly was a solid middle-class neighborhood consisting of married couples with children. Although socially homogenous, the neighborhood was home to a variety of people from a myriad of nations including native-born Americans, Germans, Irish, Swedes, Scots, Swiss, Australians, and French. Some families had live-in servants, most of whom were Chinese men or Irish-born women. Unlike the radical, rabble-rousing working class Mission District or South of Market, the Haight was known as a stable and, one might stay, stuffy neighborhood.

The local real estate sections of the local papers carried articles on the progress of development in the Haight. The March 8, 1896 edition of the Examiner reported:

The whole country about the heights is now thickly covered with homes of conspicuous size, and many of them of costly design. Masonic Avenue is lined with a large number of Eastlake dwellings, where barren sands were a few months ago. Waller Street has been brightened up very recently with several pretty structures. There are more of them on Cole Street and on Frederick Street.

The article also described the modern "electric lighting appliances" and "modern styles." All this could be yours for the price of $6,500 to $8,500 each, a considerable amount of money at the time considering that cottages on Potrero Hill were selling between $1,500 and $3,000 during the same era.

Top to bottom: The Chutes (2 images): Golden Gate Park (2 images); historic house on Beulah St,; Henry H. Haight